Land and legal is part of the Sustrans traffic-free routes and greenways design guide. It covers a number of different ways in which a traffic-free route can be developed, including the acquisition of the land, creation of a Public Right of Way, or a legal arrangement involving the relevant highway or other authority. The legal matters referred to in this section relate only to the legislation that applies in England & Wales.

Disclaimer: The information and opinions contained in this Design Guide are for general information purposes only.

This Design Guide is not intended to constitute legal advice. It should not be relied on or treated as a substitute for specific advice from your solicitor.

Key principles

- Creating a traffic-free route will usually require prior agreement with landowners.

- There are a number of different ways in which a traffic-free route can be developed, including the acquisition of the land, creation of a Public Right of Way, or a legal arrangement involving the relevant highway or other authority.

- Prior to approaching landowners, advice should be sought from appropriately qualified professionals at the early stages of development of a route, to determine the legal status of any existing route components and to decide upon the appropriate legal status desired for any proposed new components of a route. E.g. from the relevant highway or other authority, and/or from an appropriately qualified surveyor or lawyer.

- There are legislative differences across the UK, which are relevant to creating routes. Most of the legislation which applies in England also applies in Wales. Separate legislation applies in Northern Ireland and Scotland.

- The legal matters referred to in this section relate only to the legislation that applies in England & Wales. The detailed reference to Rights of Way legislation includes Northern Ireland.

12.1 Overview of land acquisition

12.1.1

Creating a traffic-free route will normally involve negotiation with a number of landowners to reach agreements to acquire the necessary legal rights and/or permissions to enable the subsequent creation of a route.

These rights and/or permissions can be acquired by outright purchase, exchange or gift of land to become the new landowner, or by leasing land from a landowner for a defined number of years, or by licence or permission granted by a landowner for a defined number of years.

Each type of legal transaction or agreement has different characteristics and it is important to understand them. Public Rights of Way may already exist and can also be created by highway and other authorities, using statutory powers. Other arrangements may potentially be feasible, subject to circumstances and requirements.

12.1.2

Landowners may have objections or reservations about the creation of a traffic-free route affecting their land.

These are more likely to be successfully resolved if each landowner is sufficiently engaged with the proposals as early as possible in the design process. A suggested process for engaging with landowners is shown in the figure below:

12.1.3

It is important to seek to acquire sufficient extent of land to enable the future construction and all ongoing maintenance of the proposed traffic-free route by the relevant parties, and without undue constraint being created at the development stage.

It is likely to be much harder to acquire more land at a later stage. It is essential to be aware of any constraints and liabilities that may already exist or which may develop in time, especially if the land is owned outright.

Areas or land acquired may be found surplus to route development requirements, and could be made available to others, potentially to generate funds, or put to good and complementary uses.

12.1.4

It should be noted that each land negotiation would, to varying degrees, be necessarily bespoke and require flexibility in the approach with landowners and councils.

12.2 Public Rights of Way

12.2.1

Public Rights of Way provide legally protected rights to pass and re-pass a route and give the public the opportunity to enjoy the outdoors. Those public rights cannot be taken away except by operation of law.

In England and Wales, Highway Authorities are (usually County Councils or unitary authorities) required to produce, and keep updated a definitive map and statement showing their Public Rights of Way.

The definitive map and statement held by each Highway Authority should be publicly accessible, either in hard copy or online.

Where an existing Public Right of Way is being improved as part of the development of a route consideration should be given to the Defra Rights of Way Improvement Plan guidelines (Defra, 2002). Paragraph 2.2.21 of these guidelines state:

"There is potential for conflict on ways carrying higher rights between different classes and types of users.

"Wherever possible proposals for improving rights of way should not unduly benefit one class of user at the expense of another. Improvements that are intended to benefit cyclists, harness-horse drivers, horse riders or walkers should not unduly restrict lawful motorised use of public vehicular rights of way."

12.2.2

The matter of Public Rights of Way in Scotland is distinct from that in England, Wales, & Northern Ireland. In Scotland, local authorities, the Scottish Rights of Way and Access Society, the public & landowners are relevant.

Public Rights of Way continue as a separate matter from the much wider rights of access, which were codified in law as one of the three main provisions of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003.

In Northern Ireland, the Access to the Countryside (Northern Ireland) Order 1983 provides that local authorities are responsible for Public Rights of Way.

Each council has a specific duty to assert, protect and keep open any Public Right of Way and to make and preserve maps and other records of the Rights of Way in its area.

The Local Authority must enforce the public’s common law rights of passage, and investigate and record where those rights exist. Local Authorities have a duty to assert, protect and keep open and free from obstruction any Public Right of Way.

The remainder of this Chapter applies only to England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

12.2.3

There are different categories of Public Right of Way as listed below:

12.2.4

Responsibilities for maintenance of Public Rights of Way are apportioned between the Highway Authority and the landowner as listed in the table below:

12.2.5

A Highway Authority or other Local Authority through a ‘public path creation agreement’ with the landowner can create public Rights of Way under Section 25 of the Highways Act 1980.

In certain circumstances, Public Rights of Way can also be created through a ‘public path creation order’ made by a Highway Authority, other Local Authority, Strategic Highways Authority or the Secretary of State under Section 26 of the Highways Act 1980.

In both cases, the resulting highway will be maintainable at the public expense. There will need to be a discussion about what type of Public Right of Way should be created (see above).

Alternatively, a landowner may seek to ‘dedicate’ their land for use as a Public Right of Way, either expressly or by presumption or by “deemed dedication” following 20 years’ public use.

Anyone who has evidence that a right of way has come into existence by statute or common law can apply for a Definitive Map Modification Order (DMMO) to have the right of way recorded on the definitive map.

DMMOs are about whether rights already exist, not about whether they should be created or taken away.

12.2.6

To facilitate cycling, it is possible to convert all or part of a public footpath to a cycle track by making a Cycle Tracks Order (CTO) under Section 3 of the Cycle Tracks Act 1984 and the Cycle Tracks Regulations 1984.

On conversion from a public footpath to a cycle track, the cycle track becomes a highway maintainable at public expense, even if the footpath had not previously had that status.

A Local Highway Authority has power to carry out any works necessary for giving effect to a CTO; in so far as the carrying out of any such works, or any change in the use of land resulting from a CTO, constitutes development within the meaning of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, permission for that development shall be deemed to be granted.

12.2.7

The proposal to convert a public footpath under a CTO may result in objections being raised.

If objections are not withdrawn, a public inquiry may be held which then requires the Secretary of State to confirm the Order, with or without modifications, or reject the Order.

Common sources of objection are landowners, who have to give consent if the footpath crosses agricultural land, and ramblers groups who may object as making the order results in the public footpath being taken off the definitive map.

12.2.8

To overcome the likelihood of objections, it may be possible to create a parallel cycle track through either dividing the footpath width longitudinally and converting half of the width under the Cycle Tracks Act or avoiding a CTO by creating a parallel permissive path for use by people on bikes.

12.2.9

It may be preferable to create a route as a bridleway. This will require provision to be made for people riding horses and may affect the width of the route, surfacing type and parapet height of bridges.

12.2.10

Agricultural and other motorised vehicles may use byways open to all traffic.

Where there is potential for this to cause conflict, proactive management to deal with the issues can facilitate sharing of the byway by all legitimate users.

‘Making best use of byways’ (Defra, 2005) provides guidance on the management of byways.

Where motor traffic speeds and flows are sufficiently low it can be possible for walkers, cyclists and horse riders to comfortably share a route with people riding or driving motorised vehicles.

This would in effect create a Quiet Lane where typically actual speeds should be under 40mph and motor traffic volume less than 1,000 vehicles per day.

In these situations, it may be appropriate to provide measures to remind all users of the shared nature of the route.

Where motorised vehicles need to be provided for this may require a more robust construction to withstand the greater loading.

12.3 Permissive routes

12.3.1

Where a traffic-free route is not being created as a Public Right of Way, a permissive path can be created with the agreement of the landowner. This is usually necessary when the land is acquired under a lease or a licence.

Landowners may prefer the creation of a permissive path, as no public rights being created allows more flexibility to divert or close the route should circumstances dictate. However, this can give the route less long-term security and vulnerability to closure in the future.

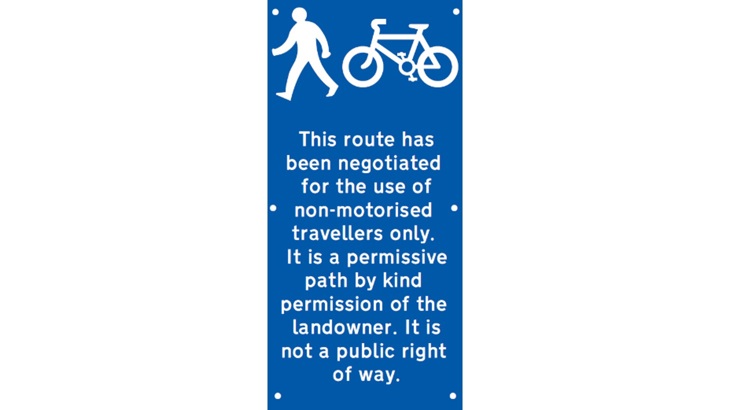

Example permissive path signing.

12.3.2

To prevent a Public Right of Way being claimed through a user, it is essential that appropriate signing, stating that the land or route has not been dedicated as such, is erected and maintained.

This is often a requirement set out in a leasehold or licence agreement.

12.4 Traffic-free routes in parks or along promenades

12.4.1

Byelaws are local laws made by a local council under an enabling power contained in a Public General Act or a Local Act requiring something to be done – or not done – in a specified area.

They are accompanied by some sanction or penalty for their non-observance.

Many parks and other public spaces have byelaws that prohibit cycling, either absolutely or in certain circumstances, and Local or Private Acts of Parliament may restrict use by people on bikes.

If amendment or revocation of an existing byelaw is necessary, this is a legal process that needs to be worked through.

Guidance for councils on making, amending and revoking byelaws can be found on the government website.

Sometimes, however, byelaws do not need amendment or revocation because what is sought falls within the scope of the existing wording. It is therefore advisable to check the wording of a particular byelaw and other legislation carefully and seek legal advice as appropriate.