Path specification details is part of the Sustrans traffic-free routes and greenways design guide. It provides an overview of construction specification and details relating to the surfacing, foundations, and edge details.

Key principles

- Construction specification is a key element of creating high-quality traffic-free routes.

- Construction details relate to the surfacing, foundations, and edge details.

8.1 Path construction overview

8.1.1

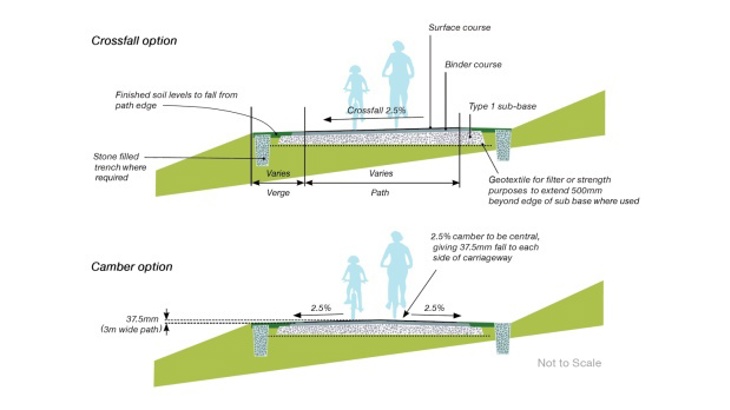

The path of a traffic-free route will comprise a surface and foundations. A typical cross-section through a path illustrating these components is shown in the figure below:

8.2 Path foundations

8.2.1

The foundations of a path are key to the quality and longevity of the path surface. Path foundations usually comprise of sub-base. This is a layer of compacted aggregate placed on the subgrade, usually compacted native ground. The purpose of the sub-base is to distribute the loads imposed on the path into the ground.

Sub-base being laid and compacted on Lumb to Iron Gate Lane path, Rossendale, Lancashire.

8.2.2

Where a path is being constructed on weak or soft ground, it may be necessary to provide another layer beneath the sub-base. This is typically known as a capping layer and consists of larger stone or crushed rock. The time of year when a path is constructed should also be considered when specifying foundation types.

8.2.3

The use of geogrids and geotextiles may enable a shallower foundation to be provided where ground conditions are poor. These systems can increase the load-bearing capacity of the existing ground. Advice should be sought from an appropriately qualified person when specifying such systems.

Geogrid being laid for Hadrian’s Cycleway, Allonby, Cumbria.

8.2.4

The thickness of sub-base should be calculated from the likely path loadings and the load bearing capacity of the subgrade. People walking, wheeling and riding bikes will impose negligible loads. So designers should calculate the composition from anticipated vehicle loadings. These vehicles may use the path to undertake maintenance, gain access to private property or for emergency purposes. Typically, a sub-base thickness of 150mm, after compaction, will be enough. This may be reduced where the subgrade is strong, or increased when soft, wet or poor native ground is encountered.

8.2.5

The sub-base should be an engineered material specified and compacted in accordance with the Manual of Contract Documents for Highway Works, Specification for Highway Works. The most commonly used is termed Type 1 sub-base, which consists of a well-graded selection of stone size from dust up to 37.5mm.

When considering a minimum layer thickness, the layer should be at least twice the size of the largest stone size. This ensures that no particle can contact the top and bottom of each layer. As this would serve to reduce the interlocking nature of the stone and create weak points in the layer.

8.2.6

Where disused road alignments are incorporated into new path construction, the disused road surface may provide a good foundation that can simply be resurfaced. If a more extensive new construction is required, it may be necessary to perforate or break up the existing surface to provide drainage.

8.3 Path Surfacing

8.3.1

The path surface is a key factor of user experience. A smooth, dry, continuous surface will provide a more inclusive and accessible route than a muddy, rutted surface. To achieve a positive user experience, a sealed path surface is recommended.

8.3.2

The quality of a path’s surface can influence the ability of a path to shed water efficiently. Hand-laid surfaces have the tendency to be less even than a machine-laid surface. This can lead to more standing water being encountered along a path. A machine-laid path will provide a more consistent and even surface. This will encourage water to shed and reduce the likelihood of ice occurring during colder weather.

8.3.3

Path surfaces are typically composed of layers of bituminous material. They can also be constructed from other materials, such as concrete. Concrete will provide a good surface in terms of being impermeable, smooth, consistent and hard-wearing. But as concrete is laid in sections, it can result in jointing at regular intervals along a route. These can be uncomfortable to some users, such as people on bikes and wheelers.

Concrete path being laid at Leicester Road Viaduct, Warwickshire.

8.3.4

Whilst less widely used, timber decking and Glass Reinforced Plastic (GRP) panels can also result in jointing along a route. However, timber decking and GRP can offer benefits when used on structures where weight saving is a factor. They can also be beneficial when used at constrained sites where deliveries of concrete or bitumen may not be feasible.

8.3.5

There are many innovative surfacing products being widely used in transportation engineering applications. These products include resin-bound aggregates and recycled rubber and plastic composites. The main draw to some of these products is their use of recycled products, as well as some of their physical characteristics. For example, some surfacing that has a high rubber content can be more flexible underfoot. This may be preferable to horse-riders and runners.

Composite rubber wearing course used on Lumb to Iron Gate Lane path, Rossendale, Lancashire.

Innovative products are currently being used on a number of traffic-free routes. However, their performance and maintenance requirements require careful consideration. As these are still relatively unknown with some products and systems.

8.3.6

Designers are encouraged to explore the most suitable path surfaces to suit the route objectives, user composition, predicted path use and budget (including maintenance). Further considerations will also include skid-resistance requirements, whether a permeable surface is required for the purposes of drainage, and whether certain surface types may serve to exclude route users. For example, horse riders may prefer not to use a route with a concrete or bituminous surface.

8.3.7

Some sealed surfaces are less desirable for horses as they can have insufficient slip resistance for horse’s hooves. A solution to this may be to provide an adjacent trotting strip, which does not need to be finished with a sealed surface.

Trotting strip alongside traffic-free route.

8.3.8

Concerns may be raised where sealed surfaces are proposed within rural areas. Their introduction could be considered to ‘urbanise’ natural environments. To alleviate these concerns, designers can specify alternative surface course materials.

For example, white quartz chippings can be rolled into a bituminous surface. This will to reduce the intensity of what would otherwise be an entirely black coloured surface. Surface dressing and other stone finishes can also be specified, and coloured asphalts are becoming more common.

Designers should also keep in mind that a new bituminous surface would lose it colour intensity with time. Photographic examples of this colour loss may be useful in managing stakeholder concerns.

8.3.9

An example specification for a bituminous path composition is provided in the table below.

8.3.10

It is important for designers to consider the drawbacks of path surfacing in terms of impact on user groups. An unsealed surface could be a cost-effective solution but its uneven and rough surface composition would serve to exclude wheelers. Conversely, a route that is surfaced using bituminous material would be smooth and even for wheelers, but it could serve to exclude horse riders. The table below outlines some of the advantages and drawbacks associated with different path surfacing types.

8.4 Path edges

8.4.1

Kerbs or edgings are usually provided to contain a path and prevent failure of the path edge from traffic loading. A large proportion of routes may not need kerbing or other edge restraints given that vehicle loadings will be minimal. Where kerbs or edging are not needed, the path should be constructed so the sub-base extends 300mm beyond the surface course on each side.

Sub-base extended beyond path edge on Lumb to Iron Gate Lane path, Rossendale, Lancashire.

8.4.2

Path edgings may be formed from pre-cast concrete edgings, timber edgings or proprietary metallic edgings. Timber edgings are considerably cheaper than other options but consideration needs to be given to providing adequate lateral support. This will ensure that the edgings are not distorted or displaced during laying and compaction of the path construction.

8.4.3

It may be appropriate to provide edgings to a path in locations where a more formal edge is required, such as through parks, or where a route passes through a public realm area.

Furthermore, visually impaired users utilise the edgings and kerbing as a means of guidance. Therefore, when designing a path, designers need to carefully consider the route environment, the needs of visually impaired users, the loadings imposed on the and ground conditions.

8.5 Path drainage

8.5.1

Standing water and surface water discharge can serve to damage a path’s surface, leading to a decline in its integrity and its serviceability. Standing water can also freeze during colder weather, creating a facility that is unpopular and underutilised due to safety concerns.

To facilitate surface water run-off, paths should have a cross-fall (fall to one side) or camber (fall from a centre line to both sides). Where possible, designers should incorporate camber to a path’s surface, as this will provide a better outcome for wheelers. Cross-fall and camber should be provided in accordance with the table below.

8.5.2

Path edgings can strengthen a route that is subjected to flooding, as the edgings will guard against washout of the sub-base and consequential undermining of the path. It is recommended that in these situations a pre-cast concrete path edging be provided.

8.5.3

The area immediately adjacent to a traffic-free route is termed the verge. A verge width of 1.0 m should be provided on each side of a path. The verges should normally fall away from the path to facilitate drainage of surface water. Verges should be kept clear of any vegetation other than grass, which should be mown and kept cut back as it will tend to encroach onto the path, reducing the effective width.

8.5.4

It is important that surface water not only be shed from the path, but that it does not pond immediately adjacent to the path. Localised ponding adjacent to a path edge may lead to flooding, ice, and mud on a path surface.

8.5.5

Similarly, if bunds are provided along both sides of a path, consideration should be given to how surface water will be allowed to drain away. In these situations, it is likely to be necessary to provide shallow ditches along each side of the path.