Active school travel could be an effective public health solution to tackle physical inactivity among children. In this post, Nafsika Michail shares the conclusions of her research on how behaviour science could inform urban design interventions to promote active travel.

Active school travel could be an effective public health solution to tackle physical inactivity among children.

Active school travel

My PhD research is focusing on how urban design could promote more active trips to school.

It takes into consideration all the various benefits of active school travel for individuals’ health, the community and the environment.

Acknowledging the multiple factors that influence travel decision making

Travel behaviour is a complex and multi-disciplinary topic.

Therefore, urban design that aims to change travel behaviour should take into consideration the multiple factors that may influence travel decision making.

This is particularly true for active school travel, where existing frameworks in literature suggest a complex relationship and dynamic interaction between individuals’ and households’ characteristics, as well as social and environmental influences. [1-3]

Children’s perception of their journey to school could also affect their travel behaviour, since active school travel is a habitual behaviour (ie, walking to school as part of a morning routine), but also a reasoned one (ie, walking to school because it is the best possible option). [4]

Therefore, behavioural science suggests that urban design interventions to increase active school travel should employ more holistic approaches.

Increasing the effectiveness of interventions by incorporating behaviour change

A promising way to make interventions more effective and sustainable would be to consider existing theories and models that focus on human behaviour and behaviour change.

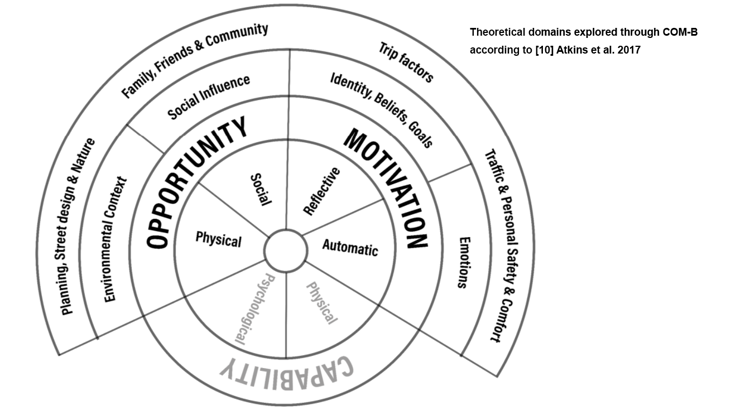

The Capability, Opportunity and Motivation Behaviour model (COM-B) and the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) are two of the behaviour change frameworks that can be used to explore travel behaviour.

This is because they both include attitude and cognate aspects of behaviours and the role of the built environment in promoting physical activity.

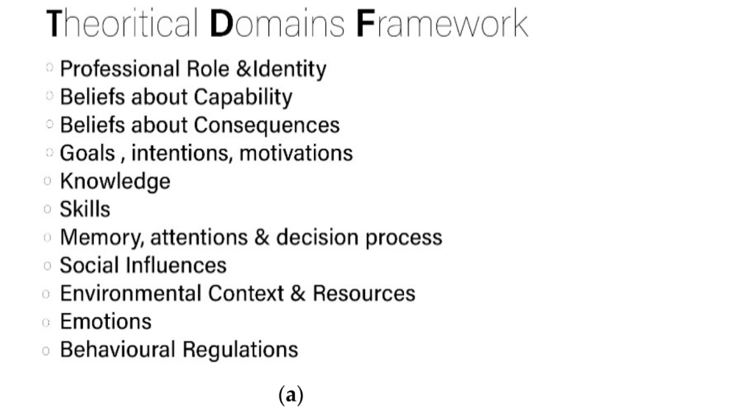

The TDF is a summary of the main domains that influence humans’ behaviour [5], including environmental context and resources, social influences and emotions (Figure 1a).

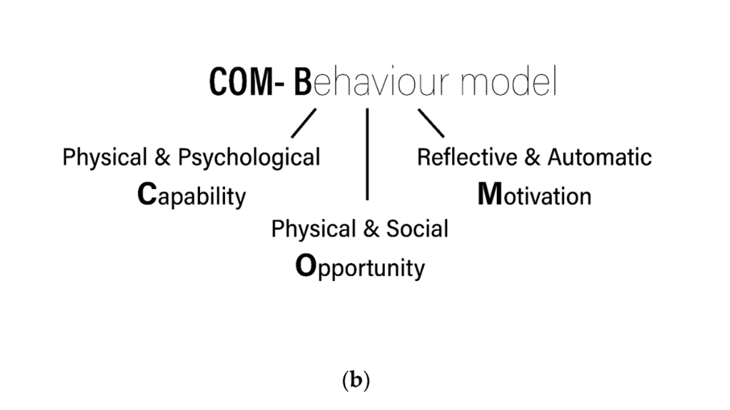

COM-B is a model currently used in different types of behaviour change interventions.

It considers human behaviour to be a result of physical and psychological capability, physical and social opportunity and the automatic (emotional) and reflective (rational) motivation to the varied influences on decision-making [6].

Nevertheless, neither TDF nor COM-B have been used to support urban design interventions.

Currently, many urban planners and designers are not familiar with them.

Children’s attitudes and their connection to behaviour change

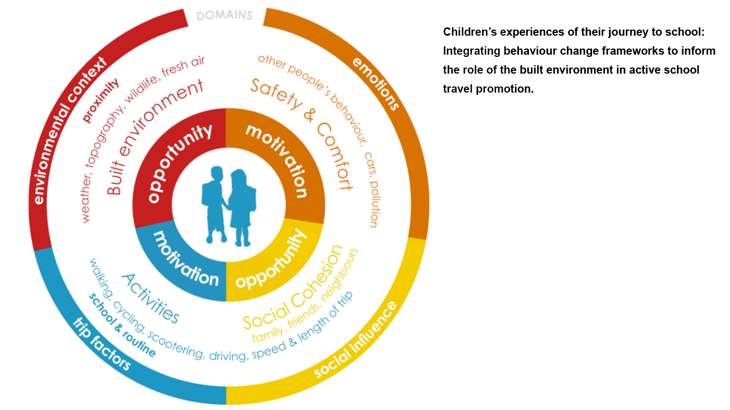

In my research, I integrated TDF and COM-B into children’s attitudes and preferences to investigate the links between aspects of the trip to school and behaviour change interventions.

The aim was to inform future urban design interventions by children’s experiences and behaviour change theories.

The study took place in five different primary schools across four different areas in Newcastle upon Tyne, between May 2019 and March 2020.

All Year 5 children (9-10 years old) described what they liked and what they disliked about their journey to school.

After a thematic analysis of children’s experiences, the themes and sub-themes were categorized according to the TDF and COM-B model, as it is shown in the figure below.

TDF and COM - Integrated to children’s themes

Children were found to prefer neighbourhood and street design that ensured street connectivity, a mix of land-uses, active travel infrastructures (like a cycling path), nature and street trees. [7]

The environmental context as an opportunity and motivation for behaviour change.

According to the COM-B model, the environmental context provides the physical opportunity to promote a specific behaviour. [6]

Evidence shows that having access to active travel infrastructure may increase walking and cycling. [8]

Therefore, planning active travel infrastructure within neighbourhoods around schools also has the potential to increase active trips to school.

It was found that children have positive attitudes towards:

- the variety of the environmental context (e.g., seeing different buildings, lack of fun places, seeing the same landscape every day)

- The opportunity to have a variety of routes to school integrating a mix of land-uses and fun places along school routes [7]

- the existence of shops, parks and front gardens along the school route that stimulate children’s senses (e.g., smelling food, hearing birds, seeing flowers). [7]

On the other hand, children have negative attitudes towards the number of streets.

These findings seem to indicate that school routes with multiple options and stimuli could provide more pleasant experiences and therefore more opportunities for behaviour change. [10]

Considering and, where possible, accommodating children’s preferences in the planning process has the potential to increase active school trips.

Further health, wellbeing and environmental benefits

Making children’s travel experience more interesting might also lead to positive emotional consequences (ie, can make children happier, less stressed). [9]

Providing routes with fresh air (eg, less traffic, more trees and pocket parks) may encourage more children to walk to school [7], while simultaneously contributing to urban nature and ecology [11,12], which in turn could enhance the multisensory experience of a school journey.

Apart from the physical opportunity for more active trips, the built environment may have an impact on other domains, such as emotions and social influence, which affect motivations and opportunities for a behaviour change.

By exploring this impact, urban planning and design could contribute to creating cities, neighbourhoods and school streets supportive of active travel among children.

For example, designing to ensure traffic-related safety may work as an automatic motivation towards a behaviour change. [10]

Similarly, a more effective design of footways and dedicated cycle lanes that enable a better segregation between different groups could provide improved experiences, since children reported negative experiences of crowded paths or interactions between themselves and other pedestrians or cyclists. [7]

Increasing the opportunity for social development

The opportunity of social interactions with family and friends is a crucial aspect of children’s journeys, regardless of the mode of travel. [7]

Similarly, interacting with the larger community was regarded as a positive aspect, especially for children walking to school. [7]

Hence, in order to enable social opportunities, the built environment should encourage a cohesive community that accommodates social interactions that pupils enjoy on their journey to school (ie, meeting/playing/talking with friends and neighbours along the route).

To achieve that, improving the physical quality of streets and public spaces, and hence residents’ environmental perception, could influence social cohesion. [13]

Conclusions

Urban design interventions that aim to promote active school travel should encourage physical and social opportunities as well as reflective and automatic motivations for behaviour change.

Besides enabling active travel, safe routes to school can provide positive experiences that may increase sustainable AST in the long term.

Carefully-designed school streets and green shortcuts can ensure safer, quieter and cleaner travel experiences for children along their journey to school, providing pleasant experiences of the urban realm. [7]

Designing for pleasant experiences and safer journeys can promote automatic motivation and positive attitudes among children towards active travel, physical activity and engagement with their local neighbourhoods. [7]

Finally, it is important to mention that in many cases, parents’ decisions for their children commuting to school may be a result of their social identity and personal priorities, which may have an impact on children’s experiences.

However, different means of travelling were found to provide different experiences. [7]

Hence, designing neighbourhoods and school streets that support no-escort trips could allow children to develop their own experiences of active school travel without depending on their parents’ social identity, which may enable a sustainable behaviour change in the long term and a cultural shift towards active travel in the future.

About the author

Nafsika Michail is a Liveable Cities & Towns Urban Designer at Sustrans, and a landscape architect currently working on her PhD focusing on how urban design could promote more active trips to school.